La Mano

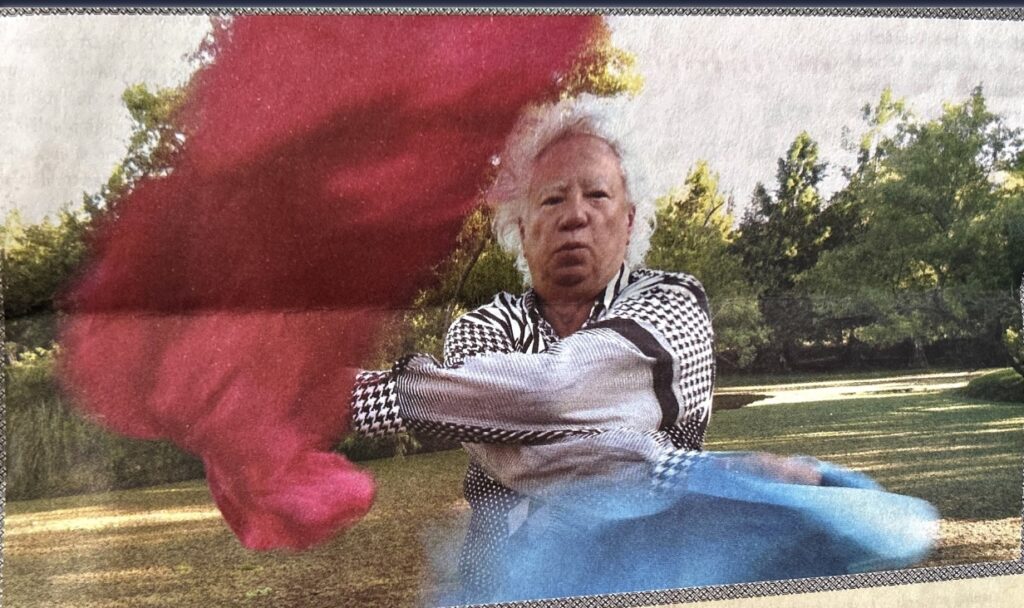

Rogelio Polesello – The permanent gaze

Nº35 – February 2007

On vacation in Punta del Este, Uruguay, Laura Batkis met Rogelio Polesello in a paradisiacal house in Laguna del Sauce. She couldn’t resist the call to duty, she took out the voice recorder and they started chatting at length about art and other matters.

He is one of the artists best known to the general public and now he is also recognized by the “intellectual elite” who discovered him as a pioneer in geometric abstraction.

Laura Batkis: You were telling me that you feel like a survivor?

Rogelio Polesello: Yes, I am a survivor. I am sixty-seven years old, I saw the beginnings of the Di Tella and I have been showing my work since 1958. I am a restless, passionate and beautiful survivor, like when I was twenty years old, and I am in conditions that fascinate me and that allow me to dream like a youngster, which is how I feel.

How do you maintain a fifty-year career, being on the crest of the wave, always in the limelight and up to date?

By forgetting that you want to keep going. You have to do everything backwards. You have to keep on doing your own thing every day, and there is something that for me is an example: I recently saw an exhibition of Lichtenstein with preliminary studies at the Malba (Buenos Aires Museum of Latin American Art) that I deemed formidable. I could see the dates, and the same thing happened to all of us, and that is that at that time we artists wanted to show the big work, the finished and exemplary work, we did not show the sketches. And I think what is happening today is that people want to know where all that came from. Hence the importance of the projects and studies that nobody showed at that time, but today they do, because that’s where you see the course of a career.

In the exhibition that was recently held at the Recoleta Cultural Center about the Collection of Banco Ciudad, there was a work of yours from the sixties that seems to be made by young emerging artists of today, do you realize that?

Yes, because deep down it’s like the artist is a monothematic. I always remember something that Alejandro Otero, a great Venezuelan artist, said, and that is that in life you must have only one good idea. And I believe that what is happening with my work is the recovery of that profound thing from when I made the first lines, where I already anticipated what was to come.

What is your first idea?

I was interested above all in building. I come from a family of Italians, Friulans, Venetians, from where everybody needed to get out of the war and build everything again. I lived around that idea ever since I was a boy, and my interest was always to build, with images or with ideas, where I was the main character. I admired the comics Harold Foster, Alex Raymond and Hugo Pratt.

It is also a construction from color and graphics. I always fought in favor of graphics, which was what had to do with my work from the beginning. But at that time talking about graphics was like something forbidden. Imagine in 1955, telling a professor of Fine Arts that you were working with graphics was like an offense. Now I realize that everything I proposed at that time has to do with what artists do today. Graphics is what remained as a permanent thing because it has to do with ideas and approaches.

In these last two years there was a new discovery of Polesello: the Premio a la Trayectoria (Prize to the Career Trajectory) from the Association of Art Critics, the success of your retrospective in the Recoleta Cultural Center. And since then collectors from all over the world are approaching, in Argentina local collectors are starting to notice you.

In Argentina, the artist has to be a pathetic character. Artists abroad live like princes, they have wonderful workshops, assistants. I think the retrospective show I did in 2005 at the Centro Cultural Recoleta was really important, because I wanted to show the relationship between the works from 1958 and the last ones, where it was only then understood the reason why I had different stages. In the latest works, which are very geometrical and distorted, this can be seen in the acrylics of the 1960s, which distorted the images.

Did you notice yourself that base idea that continues along your whole career?

Yes, I always knew it. What I lacked was the place and the precision to be able to show it.

And do you think that the public was able to notice that connecting thread?

I think that at least a some of the people understand what it was about. And I think that the text by Mercedes Casanegra in the catalog was very timely; it made a lot of things clear and, besides, the show was arranged in a way that the visitor could didactically understand the reason for everything that had happened.

They are looking for geometrical works from the sixties in museums abroad, like Julio Le Parc’s work.

One of the things that fascinates me the most at the moment is knowing that everything is going to arrive and that everything is on its way. Because I feel that I was not wrong in what I proposed from the beginning. What happens is that many people didn’t see it, as they don’t see other things. With Le Parc we were partners at school, we worked a lot together. And our interest in geometry began as a result of an exhibition by Vasarely that was held in 1958 at the National Museum of Fine Arts. I remember it as an exhibition that we should all see now, along with another by Ben Nicholson. They were starting points for Latin America, because it arrived in Buenos Aires after passing through Venezuela and Brazil. Many of those works had to do with what the trend Sofia Imbert fought to bring to Latin America. That exhibition marked me and rescued my ancestors, who had to do with Friuli and Venice in glass carving. Each artist, thanks to that exhibition, went his own way, for example Soto, Cruz Diez, Le Parc, me.

You are in a very special moment of your life, having a recognition in Argentina by critics and collectors. You are also selling well to people abroad.

Yes, that’s another thing that’s happening, that the world is interested in what happened in the sixties in Argentina, something that not even we Argentines realize. But look how curious it is, it also happened with Xul Solar: 10 years ago nobody was interested in his work, it also happened with Torres García. I think Argentines are a little slow. But luckily the world has become globalized and things work differently. It is positive to have recognition in life; we know that it is not common for visual artists. There is a bohemian way of living and dying very badly, poor and unrecognized. I don’t want to die badly or poorly, it’s a decision, and I’m doing important things so I have to be prepared for something even better, which is what is to come. That’s why I can take this break in Punta del Este and enjoy and forget about a lot of things.

To the art world in Buenos Aires, an artist vacationing in Punta del Este can seem like frivolity. Do you feel that?

Yes, I have felt it, and I don’t care what they say. I think I need what my health needs. And now I need rest, sea. I look a lot, I have all the antennas on, I take notes, I cut things out. I let myself be on that waterline, in that levitation I’m looking at here, on my vacation, at what belongs to me. It’s a necessary parenthesis. It is a luxury to be able to enjoy what I did with all my work, and what I will continue to enjoy with what I will continue to work with.

Where is your work going? There is something freer in your current work, more expressive.

Now what interests me most is the distortion of things, because I believe that in every human, being when he or she is a certain age, everything begins to be distorted, relationships are softened, everything is like a new way of looking and seeing things. One can be more tolerant. The other day I read something in a report by Charly Garcia that I found fascinating. He talks about distortion, because he says that within all this technological thing today he is still a non-technological artist. That he’s interested in the noises of the pulp records. I don’t operate any apparatus, I do everything manually and I think one of the things that fascinates me most is that I am an artisan of everything that is to come. Technology is only a tool. I liked what Charly said, that technology is something cold, anyone can do it, but he likes the human part. I’m very interested in that, that’s why my paintings have a lot of substance, defects, a lot of things that you couldn’t do in print.

You are your own company. You worked with many galleries, but you always managed your career.

Yes, I never found a gallery that outdid me. I am sure I will find it, I would like to have a representative in the whole world, not locally.

You make it, you sell it, you collect it, and you establish your own contacts in your social activity!

Yes, because I have no choice. My way of thinking is like that of the great designers, who suddenly make their designs and have different representatives in different places, then they give the representation to a certain a person. I think that’s the way artists, or artists’ galleries, should work in the future. It didn’t happen to me, but I know it exists and it works. I loved, for example, to see how all this worked at the last ARCO Madrid, where I was represented with Jorge Mara, and to see how it is done at the Art Basel Miami, in which I participated with Cecilia Torres. I think that today the artist and the gallery have to work together, not in isolation.

You have something that you find in few artists: you are not afraid of openings, nor are you afraid of mass exhibitionism.

No, not at all, I don’t have those phobias.

And how do you see yourself in the future?

I can wait as long as I want, I still have time, I know I have content, that what I have done is important. What is coming is getting stronger and stronger and is a step further, but we have to stay calm. Those young artists who are going crazy, who want to arrive soon with meteoric careers with a lack of work, that’s no good.

What do you mean by “arrive”?

To arrive would be something like continuing to work in what one believes in, and that would have a normal development. It’s not that you have to invent something every 10 minutes, because then you have a novelty fair. The good thing is when you focus on your work.

You lived the mythical sixties, were they so glorious?

I remember the sixties with much euphoria. They were incredible times. The Di Tella was fascinating, Romero Brest was a powerhouse, everything that happened had an uncommon energy that doesn’t exist today. I don’t find it even in young people now. Today everyone does their own thing individually; before it was a more of a collective experience. For me, Di Tella was my second home, I was very young, I met artists, I worked like crazy as a cadet during the day and at night I went to meetings, I met people. I insist, a lot of energy in a time when there was not the communication that exists today. The Internet works miracles, but it also buries many people because there is no time to digest.

You are not a resentful person, you always accept changes, you don’t carry that “the past was better” thing.

You have to adapt to what’s happening, the world has changed a lot. Today everything is much more dramatic and violent, so you have to accept that communication also generates changes because of the harshness and speed that shows you what is happening, and to endure you must have an emotional axis, it is fundamental.

And success?

You have to forget about success. Suddenly it’s there, but it doesn’t matter. That’s why I think I can take perhaps with a little frivolity this thing of the world of art. Success isn’t necessary, it’s not good for anything, but when it comes you have to know how to take it. It doesn’t last either, you have to take it like a good meal and that’s it, like: “today I had a good champagne, tomorrow I start the diet again”, go back to work, start again and that’s it. Do not live on nostalgia.

What is art to you, what is it that you do?

Sometimes I don’t have the slightest idea. I know that when I was born I earned an eternal scholarship. And I follow it because I love it. To be born with a sensitivity to decant the things I like and to relate them is amazing, in the end that is what art is, to relate one thing to another, like the thinking eye, and when that encounter takes place there is a spark, then there is art.

BY LAURA BATKIS