La Mano

Jorge Macchi – My Approach to Art is Romantic

No. 29 – Buenos Aires, August 2006.

He is the Argentinean artist who gave identity to the imminent São Paulo Biennial, since one of his artworks was chosen as the institutional image of the event. Laura Batkis went to his workshop and they talked for a long time.

Today, Jorge Macchi (1963) is the most internationally sought-after Argentine artist of our time. Twenty years ago, he began a career which slowly matured an identifiable image. From his beginnings, with his painted domes to the newspaper clippings of today, there is a common thread that is repeated, it is the evidence of absence. Two of his works are part of the Tate Modern in London and he represented Argentina at the Venice Biennale last year.

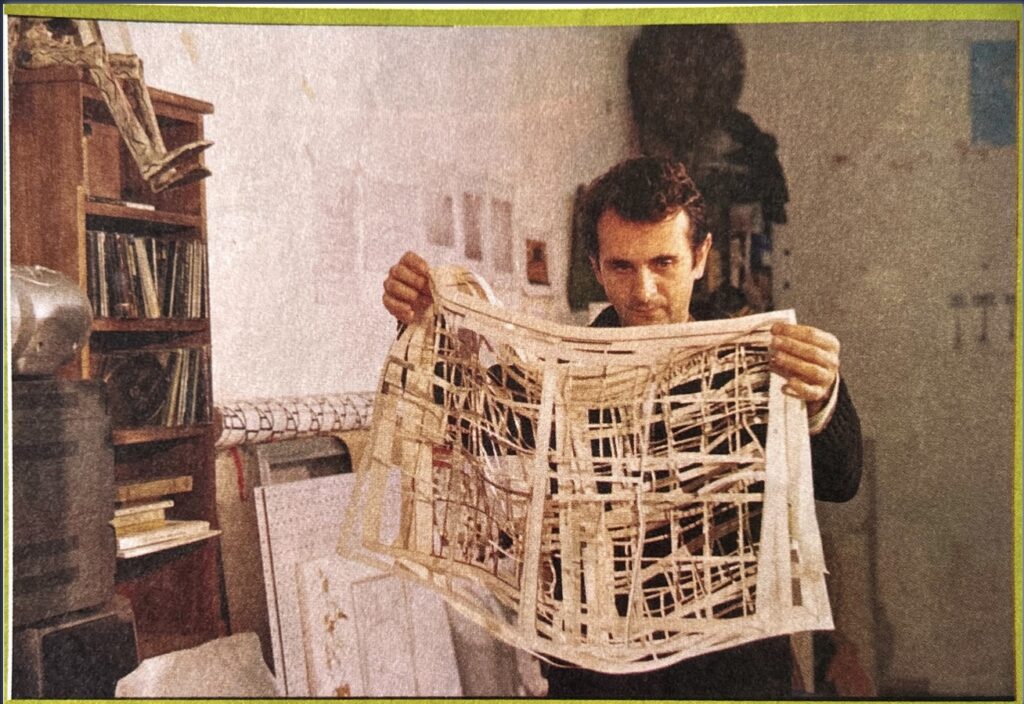

His Boedo workshop has an almost monastic austerity, he takes his time and speaks slowly, while the conversation is interrupted by calls from his international marchands. Here is what a modest artist says that reveals with extreme romanticism the nostalgia of the lost paradise, without stridencies, with the distant tone of a conceptual format.

Laura Batkis (LB): What does your presence at the São Paulo Biennial consist of?

Jorge Macchi (JM): This year, unlike other biennials, there are no national entries. There is a general curator and a curatorial team of five others, among them Rosa Martinez, who last year was the curator in Venice. This team selected Eloísa Cartonera and León Ferrari. My participation is not with artworks exhibited in the pavilion, but I am present with the design of the poster, which was for a competition. They gave you the name of the Biennial, which is “How to live together”. I sent an image proposal, a detail of the work “Speaker’s Corner.” And I won.

LB: Your work will be the cover of the catalog and the giant poster that marks the entrance to the venue. How did you choose it?

JM: I design posters for plays. Last year, I did the poster for the International Theatre Festival in Buenos Aires. When I think of an image for a poster, I try not to illustrate the event, and that somehow it can open new readings. The point is that from the encounter between this image and the event, one inevitably begins to establish links.

It is like the phrase of the Count of Lautréamont used by the Surrealists: “Beautiful as the fortuitous encounter between an umbrella and a typewriter on a dissection table”. “Beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.”

It’s something like that. The interpretation they gave was, “Wake up; the festival is coming.” I never thought that, but somehow that image is related to the event, although perhaps no one really knows why.

LB: In the case of the Biennial I think it is more illustrative.

JM: I don’t know; why do you say that?

LB: Because in “Speaker’s Corner” there are many people talking together, and the theme is living together.

JM: No. There are many speeches together, but there are no people. And what I think is happening in that work is that there is a bit of a paradoxical situation because there are many discourses together, but we only have the quotation marks, and the content of the discourse is absent. So on the one hand there is the coexistence of those discourses, and on the other hand, the emptiness of those discourses… Since the text of each sentence is absent and only the quotation marks are left, all the discourses are at the same level. It is a little ambivalent.

LB: Like what is happening today.

JM: No, I would not take sides in that sense, I am not interested.

LB: And what is your interest?

JM: My interest is that I like the image and the relationship that exists with the title of the Biennial.

LB: You are also participating in a publication that the Biennial is creating.

JM: Yes, this Biennial has the particularity of starting a few months earlier with the participation of resident artists. And all of them will make works that will be published in a book where there will be an image of one of my works, which I made especially for it. It consists of three superimposed pages from a guide to the streets of Sao Paulo. On each page there is a cemetery. I emptied all the blocks on the three pages and left only the cemeteries.

LB: How did you start working with newspapers?

JM: Between 1996 and 1997, I was in Europe. When I arrived in England, I was convinced that I would learn English, and I started reading books and newspapers in English. Then I began to notice the news of murders and police; they kept drawing my attention and so I gathered them. With that material, I made the version “Música Incidental” (“Incidental Music”), which is now exhibited as part of the permanent collection at the Tate Modern in London.

LB: And you started to put together other texts like the obituaries.

JM: Something happens that is not only the text, but the relationship between that text and the medium. The newspaper is waste material, you read a piece of news and the newspaper is already old, so you throw it away.

LB: You take the discarded material and transform it into a museum piece.

JM: I think there is a common thread in all my work: this transformation of the marginal or what is discarded, just as I used wood and metal at the beginning. The stories I take from the newspapers are also disposable because they are stories that one reads and immediately afterwards forgets. In crime news, there are several phrases that are repeated, like “a pool of blood.”

LB: You use the figure of the double a lot, I mean, parallel lives and Doppelgänger.

JM: The word “doppelgänger” refers to the idea of the double, and the myth that if you find your double, you die. It is a romantic idea. There’s a text by Poe about that.

LB: Yours is romantic conceptual art.

JM: I’d relativize that a little bit. I use materials that are from conceptual art, but my approach is romantic.

LB: There is an aspect of conceptual art that considers a project to be a work of art.

JM: I don’t agree. The project of a work is a project. The work is the materialization of that project.

BY LAURA BATKIS